Pornography, as a visual medium, has long followed the lead of technology. First it was drawn by hand. Then it was photographed. Then it was shown in back rooms on 8mm one-reelers. Then it was shown in movie theaters. Then it moved to video cassettes and DVD. Then it arrived on the Internet. Then, in the age of Pornhub, it exploded on the Internet. That’s when porn-on-the-computer innovation became the all-porn-all-the-time revolution.

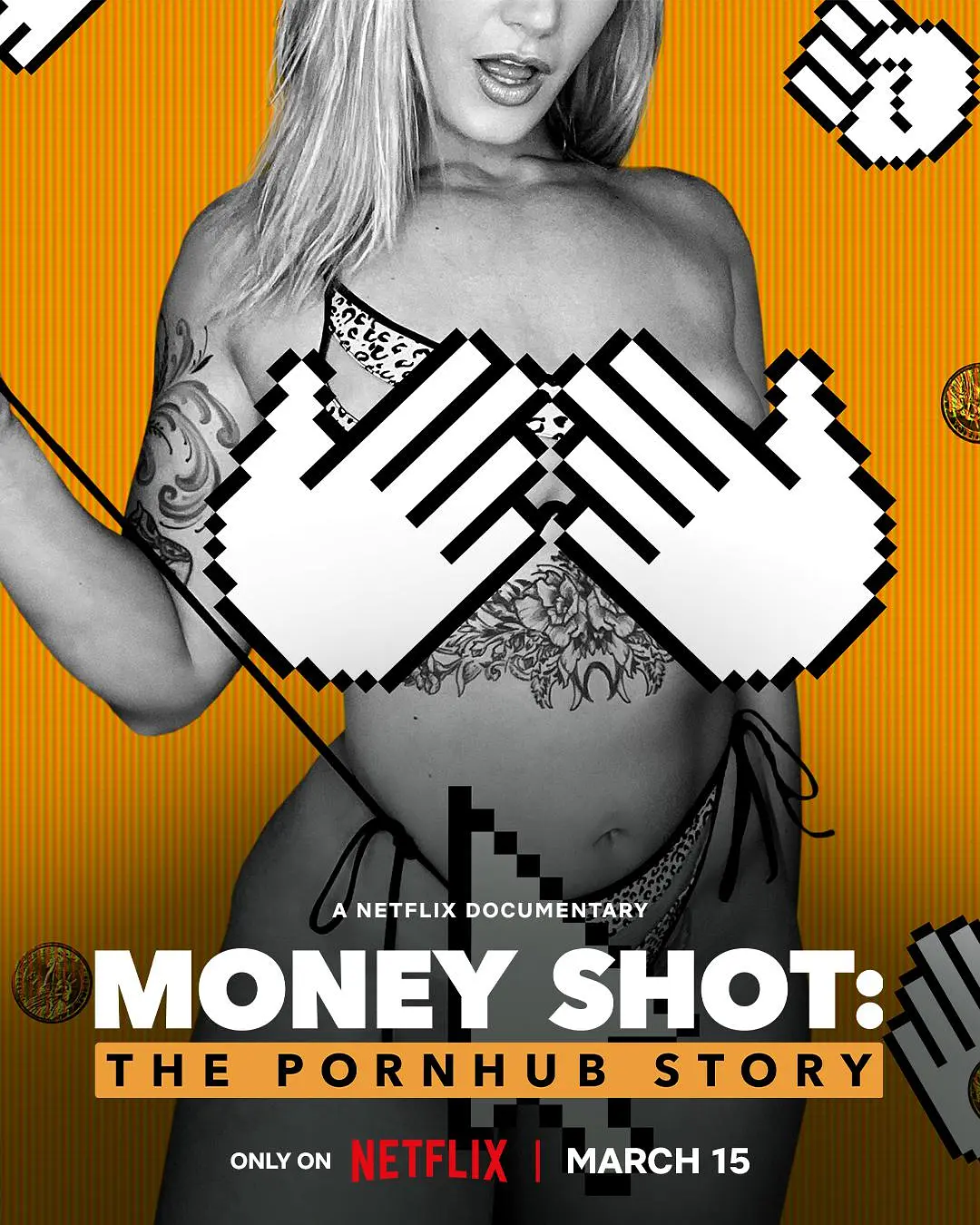

“Money Shot: The Pornhub Story,” a documentary that explores this mostly in the service of telling the story of how Pornhub, the largest porn site in the world, became a lightning rod of controversy when it was accused of being a place that abetted sex trafficking and the sexual abuse of children.

It is an ambitious investigation told through multiple fascinating interviews and dealing with a tangled web of issues that include the non-consensual uploading of intimate content, the impact of censorship on sex workers and even human trafficking. It does well to resist easy binaries and unnecessary moralising – though by the end, does buckle under the weight of the legal complexities it’s attempting to tease out.

Still, porn’s always kind of interesting.

The film opens with a strictly-business portrait of how Pornhub, about 15 years ago, became a game-changer in the world of online adult video. Porn was already thriving on the Internet, but never before had there been this kind of vast, seemingly endless supermarket of explicit material. Pornhub featured literally millions of videos, some linked for pay to the sites of sex workers, but the vast majority posted anonymously, and for free. Along with profusion came variety: seemingly every category of kink and taboo, all just a click away.

Did a site like Pornhub represent the normalization of extreme porn? I’d argue that it did. But it was in the Internet age that porn, even as it was becoming more kinky and fetishistic and extreme, evolved into a corporate entity. Pornhub is a subsidiary of MindGeek, a company privately owned in Luxembourg but based in Montreal, and as “Money Shot” captures it was run like a tech corporation. The company’s steel-and-glass offices, replete with managers in cubicles and an HR department, were comparable to those of any other tech company. The Pornhub site gets 3.5 billion visits a month, more than Netflix, Yahoo, or Amazon. It has marketed itself with a billboard in Times Square, and much of its profit comes from advertising (it has 3 billion ad impressions a day). The site is run a lot like those other Internet behemoths — it’s all about data, media marketing through search-engine optimization, and mining the tastes of users. The real Pornhub revolution was that every viewer of pornography would now be viewed as a consumer.

We meet a few of the sex workers who market videos and interactive services on Pornhub, like Gwen Adora, who describes the one-woman-band aspect of her business, or Siri Dahl, a porn performer who talks about how her earnings shot up when she began to use the site. As a de facto global mall of porn, Pornhub exerts a capitalistic energy that filters down, in an empowering way, to the workers who attach themselves to it.

The dark side of Pornhub is that its anything-goes buffet-of-kink format allowed it to become a haven for videos that depicted trafficking victims, child sexual abuse, and rape. The site was attacked — first by activists led by Laila Mickelwait, then by Nicholas Kristof of The New York Times, who has spent years in a crusade to shine a spotlight on the horrors of sex trafficking. On Dec. 4, 2020, Kristof published an op-ed piece in the Times, entitled “The Children of Pornhub,” that blew the issue up into a phenomenon. For a moment, it seemed as if the Pornhub revolution might collapse in on itself.

Kristof called for a greater moderating of content, for prohibiting downloads, and for allowing only verified users to post videos. He also called for the corporations that do business with Pornhub — notably the credit-card companies — to end that relationship, which sounded like a potent form of boycott. Due to public pressure, most of them did. But the documentary makes the point that the main people hurt by that were the sex workers on Pornhub. The site itself makes most of its money from non-corporate banner ads.

Of course, the larger issue is: What kind of content should a company like Pornhub be allowing on its site? And this is where the freedom of technology becomes tricky. The Pornhub executives initially reacted to the protests by taking down close to 10 million videos. That was in contrast to the company’s previous slow-to-non-response when individuals who claimed that they’d been filmed in non-consensual situations had to endure those videos being out there for years. But the web has a whack-a-mole aspect: Even when videos were taken down, they would often by reposted. And the documentary testifies to the extraordinary challenge of assigning moderators to weigh, and approve, the content of a site like Pornhub. (It’s analogous to the challenge of trying to scrub misinformation off the hydra-headed beast of social media.) It also emerges that some of the protests against Pornhub, arguing that the site should be shut down, were allied with the Christian anti-porn movement, which comes from a very different place than simply the policing of crimes.

In the end, there was a backlash to the backlash against Pornhub. And “Money Shot,” with a no-fuss journalistic evenhandedness, makes the case that the reaction against the site, though most of it came from an unassailable moral place, may have been out of balance — that it wound up hurting sex workers without actually doing anything tangible to help the victims of trafficking. That said, maybe the ultimate point to be made in the era when even extreme porn is now mainstream is that, as one tweet featured in the film puts it, “If you think Pornhub is bad, you’re going to REALLY hate where people go if it’s shut down.” That’s a crudely dramatic way of saying that in the no-boundaries world of the web, you can police a company like Pornhub but you can’t make what it’s selling go away.